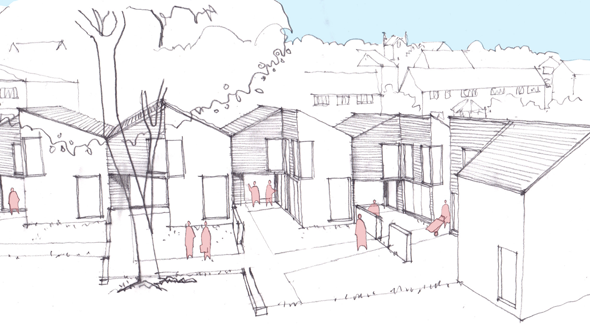

A young family in Scotland looked to update their home as their lives advanced, at the same time as their own retired parents were looking to downsize, which provided the perfect genesis for an innovative multi-generational home. Nestled in the picturesque Stirlingshire countryside, the extended family had a dwelling built that comprises a double-storey cottage for the growing family, adjoining a flat that accommodates the grandparents. Although mostly used as separate dwellings, a dividing internal wall can be opened up to connect the lounge of the main family house with the dining and kitchen area of the grandparents flat, creating one large living area. Faced with the same economic challenges as many other young families, the ageing parents were able to provide the land to build on, and their younger family provide the ongoing care and support the grandparents need. Both generations of family can now help each other through the different stages of their future lives, exemplifying and strengthening the importance of family bonds.

In a vastly different model of co-housing, Breath Architecture has produced a community led apartment complex, Nightingale 1, in suburban Victoria. Designed in keeping with the industrial character of Brunswick, the development has a strong economic, environmental and social agenda. Nightingale 1 has been born out of the “German Baugruppen movement”, a model which excludes developers, instead bringing together dwellers with parallel values to collaborate and fund their own multi-apartment housing development. The arrangement of this socially-sustainable complex combines private apartment spaces with larger shared spaces, including a communal rooftop garden and laundry. With urban densification on the rise, Nightingale 1 is a progressive model that addresses economic and environmental struggles head on.

Charles House, by Austin Maynard Architects, follows the very particular brief provided by their Melbourne-based clients that aims to accommodate necessary adaptions in living arrangements throughout the various stages of the family as they age, grow and dwindle. With the family’s intention of living in the home for a minimum of 25 years, the innovatively designed dwelling embraces life phases, with the ground floor easily adapting to become a self-contained granny flat for the grandparents, or for when the children turn into young adults. The deconstructed home knits the character of different spaces together through the easy adaption of its structure. In common with the case studies above, Charles House is a smart approach to future-living.

Although directed towards separate dwellers, in different locations and with diverse intentions, a clear social communal agenda is common to co-housing. There is a significant focus on creating strong, resilient and healthy communities of families, friends, and like-minded inhabitants for a thriving future.