‘A Stitch in Time – Guidance Notes in Maintaining your Place of Worship’

Guidance Note 1 – The Roof Covering

All of the following roof finishes require to be maintained, and obviously they all have limited life expectancies. It is essential that these roof materials be inspected regularly so that areas where water may be leaking into the underlying fabric can be repaired quickly to offset the need for more extensive and costly future repairs.

Slate

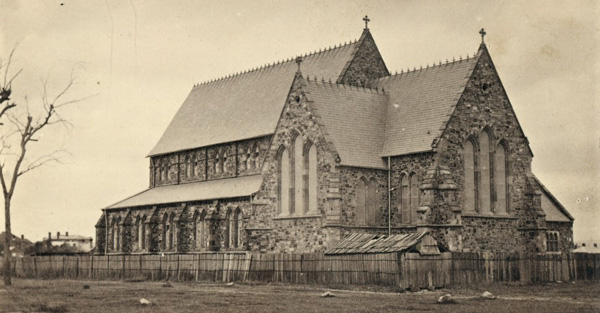

Slate has been used as a roofing material throughout the UK since the 13th century. Although slate was discovered in South Australia in 1840 at Willunga it continued to be imported from quarries in England and Wales to roof early churches in the State.

The clay can wash out leaving holes, while iron pyrites rust leaving brown marks down roofs again leaving holes where water can seep in. Once holed the slates are weakened and are prone to break, as they will also do if too thin.

Slate was commonly used in churches built early in South Australia’s history as it was the standard roofing material on UK churches at that time. Good quality slate was originally used on both of Adelaide’s Cathedrals but poorer quality slate has since been used on both during the 20th century, as it has been on many of the State’s other historic churches during the same period. As the result much of South Australia’s ecclesiastical heritage requires significant repair works if it is not to deteriorate quickly.

The key to good maintenance is to understand how to judge the condition of a slate roof so that action can be taken quickly should repairs be required.

A well-constructed roof using good quality slate that is maintained properly will protect a church for more than 150 years.

A poor quality slate roof that is not maintained adequately may need to be renewed within 30 or 40 years of installation.

Terracotta Tiles

Terracotta clay tiles have been used in Europe since Mediaeval times. Originally made by hand, these tiles are still popular today because they lend themselves well to manufacture by machine and require less skill in fixing them than slates do.

There are a variety of different profiles of traditional clay tiles. Plain tiles are simple rectangles, some flat while other are curved longitudinally. More popular in South Australia are the Marseille-style tiles imported from France after 1890 with local manufacture only starting in South Australia in 1922.

Traditionally terracotta tiles with nibs were hung over horizontal timber battens or were nailed into position, or both.

Terracotta tiles are often associated with Roman Basilica-style churches such as where designed by Walter Bagot in the 1920’s and 30’s (Calvary Chapel, North Adelaide and St. Raphael’s, Parkside are two examples).

Terracotta tiles are durable but have a limited life-expectancy. This will vary according to environmental conditions and how they are detailed in a building but generally they can last upwards of 50 years. Eventually, though, they become brittle and break with movement or under point loads, especially if located near a coastal environment.

Metal

Corrugated sheet metal roof finishes became common in South Australia only after the 1850’s when corrugated iron started to be manufactured in large quantities in the UK. Metal roofs provided a cheap and easy alternative to slate but the material only lasted 40 to 50 years. It was widely used because it was cheap, could span wide distances without requiring the supports needed for slates and tiles, and did not require to be fixed by specialist tradesmen, part of the reason why slating skills have been largely lost in South Australia.

Traditionally galvanised and steel roofing was supplied in sheets of 6-foot length. It is generally very durable, but like any other material it requires maintenance. The most common problem is rust which develops where water is trapped, at overlaps between sheets and where water is allowed to build up where gutters aren’t regularly cleared. This rust is likely to be concealed so any sheeting over 50 years of age should be closely inspected for deterioration.

Where rust is superficial it may be possible to treat it and to coat the sheeting with a suitable paint system recommended by a reputable paint manufacturer. This may offer the roof up to 15 years additional future life.

Great care needs to be taken when renewing flashings and gutters. If incompatible metals are used more rapid deterioration of the roof finish will occur. Please refer to the Guidance note on flashings for more information.

Asbestos Shingles

Due to an abundance of the raw material in Australia asbestos was used in a wide range of building components. Because the material is fire and rot-proof it has been commonly used in roofing materials, in shingles and sheet form, from the 1950’s to 1990’s. Health and Safety regulations now require expensive, specialist repairs and removal of asbestos materials.

It is very important to understand when you have a roof finish that incorporates asbestos as prosecutions can result from asking others to work on roofs containing asbestos materials, even when you were unaware of its presence and/ or the implications of exposure.

Conclusion

This guidance note is only intended to provide advice on what to look out for when reviewing the condition of your place of worship. Should you be in any doubt about the condition of your church roof please don’t hesitate to contact Arcuate Architecture and we would be delighted to assist you.