‘A Stitch in Time – Guidance Notes in Maintaining your Place of Worship’

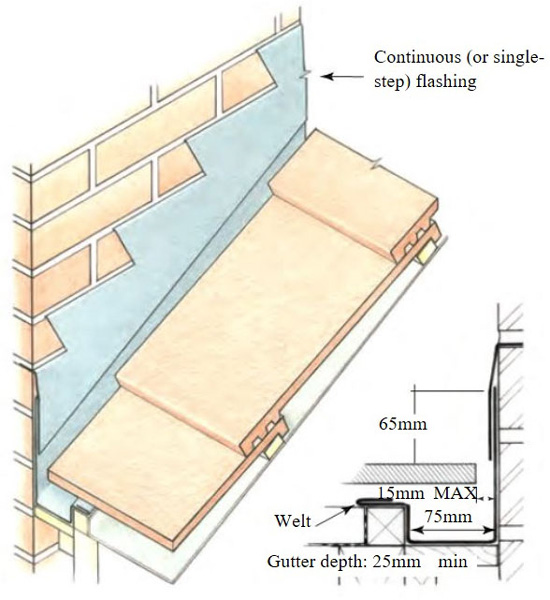

Guidance Note 2 – Flashings

On slate and tiled roofs lead was traditionally used. It is long-lasting (over 150 years if detailed correctly) but expensive to repair or replace. Lead has now been largely superseded by galvanised sheet steel for renewing flashings but it is susceptible to rust and requires to be replaced within 50 years of installation.

It is essential that flashings be in good condition. Damaged or missing flashings leave the fabric beneath vulnerable to the ingress of water. It is as important to inspect the flashings as it is to inspect the roof finish.

Conclusions

When inspecting the condition of historic church roofs it is easy to overlook the flashings, even though they are often installed at the places on a roof subject to the heaviest flow of water.

It takes experience and knowledge to understand what to look for when assessing whether flashings are fit for purpose. This guidance note provides advice on some points to look out for.

If you are in any doubt about the condition of your flashings, or of your church roof in general, contact a well-respected heritage architect who has experience in dealing with church buildings to advise on a suitable course of action.