Historic Churches in South Australia

Lessons learnt from Wooden Poles!

In the 1970s Great Britain erected over 5 million wooden utility poles to carry power and telephone lines. Now a large percentage of these are ageing beyond their life expectancy.

This issue is compounded by the fact that most of these wooden poles where erected around the same time, are made of the same materials, have the same rot treatment (creosote) and are generally exposed to the same environment.

Wood utility poles that are over 40 years old are prone to decay. As a consequence of poor foresight, and of inadequate inspection and maintenance regimes, optimistic estimates show that up to 25% of Great Britain’s utility poles are unsafe and need to be replaced as a matter of urgency.

What does that have to do with us, I hear you say?!

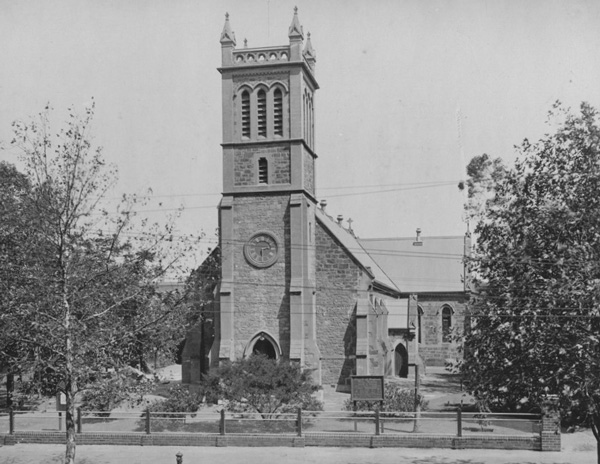

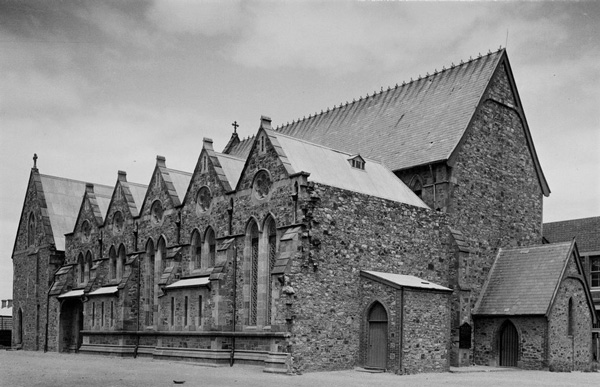

South Australia, colonised as a British free-settlement, became a sanctuary from religious persecution from the day in December 1836 when the first bemused immigrants waded ashore at Glenelg.

Hundreds of churches were built in South Australia during the reign of Queen Victoria and Adelaide became known throughout the world as ‘City of Churches’. Based on British designs and constructions, most of those churches are now the gems in South Australia’s heritage crown.

Many of the repairs carried out to historic churches in South Australia throughout the last century, especially following the Second World War, used modern materials like cement and asbestos. They have left us with a legacy of degraded church fabric and expensive remedial works.

Rather like the British wooden utility poles, South Australia’s early historic churches where erected around the same time, are made of the same materials, have had similar treatment (a legacy of poor repairs) and generally have been exposed to the same environment throughout the State. Few, if any, have been comprehensively repaired using good traditional building practices and natural materials. All are understandably showing the signs of old age and poor, if well-intentioned repairs.

South Australia, with a legacy of only 180 years of church building, needs to learn lessons from the past, and from the UK which has been looking after it’s church buildings for over 1,000 years.

South Australia needs to wake up and start taking seriously its responsibilities in conserving it’s valuable heritage of church buildings, otherwise, like British utility poles, South Australia’s historic churches will become unsafe and need to be replaced as a matter of urgency within the next fifty years.

The Author, Ian Hamilton is a Heritage Architect. He has worked on over 25 major projects involving churches and Cathedrals in both the UK and South Australia and now runs Arcuate Architecture based in Adelaide.

Ian has coordinated three major conferences in Adelaide tasked with assisting churches in South Australia with the repair, conservation and development of their places of worship.